|

Berman copied the missive to three of his superiors--HCL director

Charles Brown, technical services manager Sharon Charles, and

technical services assistant manager Elizabeth Feinberg--and didn't

give it a second thought. After all, he wrote several of them every

week. As he saw it, the note was simply a response to a memo that

had been sent around the week before concerning pending changes in

how the HCL handled the business of cataloging library

materials--that is, how the county's 26 libraries organize and

classify books, periodicals, videos, CDs, and other media for

patrons to find when they search the online catalogs. As the chief

in charge of cataloging operations, Berman figured the higher-ups

spearheading the project might want his two cents worth on the

matter.

Image By Jackie

Urbanovic | But a few weeks later,

Berman's supervisors, who have office doors that close, tapped him a

little note in response. It was five paragraphs long, but had a more

clipped tone than his January 18 memo: It was a formal, written

reprimand. Brown and Feinberg informed Berman that they viewed his

communiqué as "inappropriate" and that it constituted a violation of

the county's Human Resources Rules of Conduct. They advised, "You

have the right as a citizen to express your opinion. You may not

initiate discussion of that opinion on work time nor route that

opinion to staff at work." And they cautioned that "further

counterproductive behavior" would prompt "further discipline."

Three paragraphs, or five, can change a man's life.

The avuncular, 65-year-old Berman wasn't ready to leave his

$59,000-a-year post yet, but as events unfolded in the months after

composing his memo--his push to have the reprimand withdrawn failed,

after which he was reassigned without prior notification to a

different position--wound up resigning, in disgust. Still bitter

about his departure from the library system he'd helped build into a

nationally distinguished model, Berman calls the exit a "forced

retirement."

These days

he has plenty of time to be padding around his Edina house in socks,

an "Alternative Library Literature" T-shirt, and blue jeans. The

shirt commemorates the most recent edition of the biennial journal

Berman co-edits, one devoted to compiling cutting-edge material on

library-related issues; the comic-strip-art cover parodies a pulp

paperback and depicts a 1930s-style raid by cops bursting in on an

illicit backroom publishing operation. From his closetlike home

office, equipped with two Olympia manual typewriters, Berman is

leading a one-man retribution campaign. Since late February he's

been steadily photocopying any and all documents related to his

departure from Hennepin County--memos, printouts of e-mail,

declarations of support, letters of outrage to the library

administration--and stuffing them into bulging envelopes to send out

to friends, colleagues, the library press, and kindred spirits

around the nation: his own guerrilla clipping service. These days

he has plenty of time to be padding around his Edina house in socks,

an "Alternative Library Literature" T-shirt, and blue jeans. The

shirt commemorates the most recent edition of the biennial journal

Berman co-edits, one devoted to compiling cutting-edge material on

library-related issues; the comic-strip-art cover parodies a pulp

paperback and depicts a 1930s-style raid by cops bursting in on an

illicit backroom publishing operation. From his closetlike home

office, equipped with two Olympia manual typewriters, Berman is

leading a one-man retribution campaign. Since late February he's

been steadily photocopying any and all documents related to his

departure from Hennepin County--memos, printouts of e-mail,

declarations of support, letters of outrage to the library

administration--and stuffing them into bulging envelopes to send out

to friends, colleagues, the library press, and kindred spirits

around the nation: his own guerrilla clipping service.

When those mailings in turn generate stories in trade

publications such as Library Journal or still other letters

of protest, Berman copies those and stuffs them in the mail, too.

With each, he encloses a typed note or, often, simply his scrawled

S. He is afflicted by what one fellow cataloger dubs a

"compulsive" need to bestow information on anyone and everyone he

thinks might find it beneficial. Retiring, it seems, hasn't cured

him a bit. Berman recognizes the fixation--the very trait that

triggered his resignation. "I can't have information I know would be

of use to someone and not share it," he's been quoted as saying,

with not a hint of remorse in his voice.

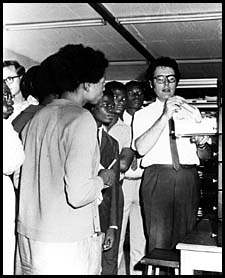

Berman on the

intricacies of card cataloging at the University of Zambia

Library, circa 1969

Courtesy of Chris

Dodge | Berman's cramped study

also serves as a storage vault for the bookmarks of his career,

including the 597-page, two-volume thesis he wrote for his master of

library science degree at Washington, D.C.'s Catholic University of

America, Spanish Guinea: An Annotated Bibliography, circa

1961. Berman allows that, indeed, he went a little farther with it

than did his classmates with theirs: "Some of them actually got away

with doing a 50-page index of a parish newspaper!" he remarks,

arching a bushy eyebrow. "It didn't seem like rigorous scholarship."

Rigorous might be an understatement for Berman's cloth-bound tomes,

which could knock a person out with a well-placed blow.

Berman's large-framed, squarish glasses, white beard, and

swept-back froth of hair give him a professorial air, and he has a

publishing record to support the impression. His shelves also hold

copies of several books Berman has compiled, contributed to, or

written, such as his 1981 collection The Joy of Cataloging:

Essays, Letters, Reviews, and Other Explosions, and one book

about him: a compilation of tributes from 1995, Everything You

Always Wanted to Know About Sandy Berman but Were Afraid to Ask,

co-edited by two of Berman's HCL cataloging colleagues, who are

known in library circles as "Sandynistas."

Turn from the shelves and you'll face a chaotic wall plastered

with laminated buttons ("Honorary Gay Man," "Wellstone," "Black

Feminism Lives"), photos, clippings, bumper stickers ("Sanford

Berman: 20 Years of Service"), notes, ephemera, and anything that

seemed, to his mind, worth saving. And there, amid the memories,

hang the awards he's received: Minnesota Librarian of the Year in

1977, the American Library Association's Equality Award in 1989, and

the Honeywell Project Anniversary Award for Peace and Justice. The

latter, from 1988, bears a quote by Mahatma Gandhi that's become a

favorite of Berman's: "Even a single lamp dispels the deepest

darkness."

His trusty Remington, from his old office, has itself been

retired to this address, to the garden in the back yard, where it

has been plopped into the rain-drenched dirt--either as a tombstone

of sorts or as a trophy commemorating his 26 years as perhaps the

nation's most outspoken, revered (by some), and irritating (to

others) champion of the public library's duty to preserving free

speech, access to information, and an uncensored press. More than

two months after announcing his untimely resignation, Berman still

sounds a bit puzzled as to how the whole controversy started. "All I

did," he offers with a sigh, "was write a letter."

«PREVIOUS

PAGE || NEXT

PAGE»

| 1

| 2

| 3

| 4

| 5

| 6

|

|